What does smoking have to do with her neck, though? Well, I'm an educated professional, so I took the time to research and find out.

Nicotine and Pain Research

As I found, research to do with nicotine and pain hasn't been extensive, probably due to "SMOKING CAUSES CANCER" being just about all we realistically should ever need to know about the stuff.

Regardless, there were many small studies that I could find that examined the relationship on nicotine and pain. Unfortunately, many of them conflict with each other and can't seem to come to a consensus. However, there were a couple conclusions to draw.

Don't People Say Smoking Dulls Their Pain?

It's true that, often, people turn to their cigarettes to deal with pain - both mental and physical. It's true that some studies have found nicotine to bind to certain receptors that potentiate pain and help to block pain signals. However, this effect, from what I can find, is not long-lasting. Also, most of the research done on this subject has used habitual smokers as their tests subjects, meaning that these individuals were already addicted to nicotine in the first place. So that raises the question: Could there be an effect of nicotine on pain outside of the window where this initial pain-relief effect occurs? It's quite possible that pain may have been potentiated in the first place by withdrawal symptoms. Also, it's been suggested that an increased pain tolerance in smokers may actually be due to detrimental damage to nerves, rather than simply being harmless signal blocking.

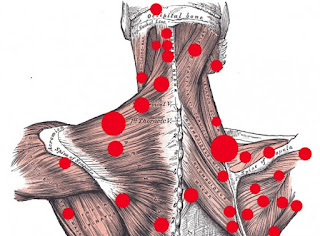

Nerve Pain

Studies about smoking and neurogenic pain (such as sciatica or whiplash pain), on the other hand, has shown some more definitive conclusions.

The first study I found wasn't completely reliable, as it only used two individuals as subjects, but it was interesting that both subjects rated their pain to be significantly higher directly while they were smoking. Patients with fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathy also reported an exacerbation of symptoms when smoking than when not. Finally, one very appealing experiment looked up close at the sensitivity of nerves, using rats as the subject. This one found strong evidence that nicotine very much increased the hypersensitivity of nerves that have undergone injury or irritation, meaning that if a preexisting nerve condition exists, the pain would definitely be more severe.

Conclusion

It's still not easy to say exactly what the effects of smoking on pain are. Like I said, there's strong evidence that pain tolerance in habitual smokers increases when they get their fix, but the mechanism of how it works may be due to some rather unhealthy effects. However, the research definitely seems to agree more when it comes to nerve pain, with nicotine found to increase pain and other symptoms of neurological disease.

To conclude, smoking is bad for you. Go tell everyone.